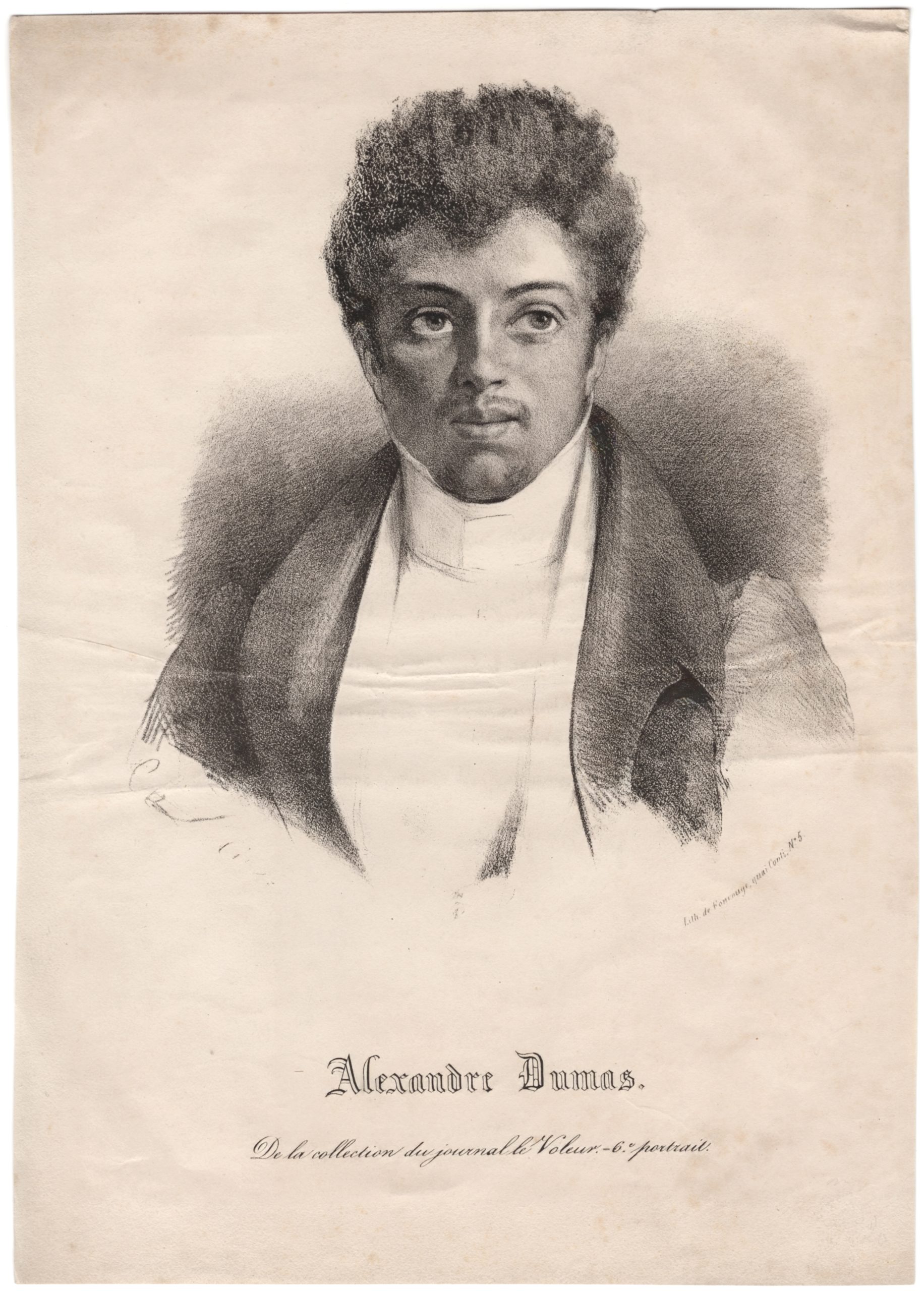

In 1834, as Alexandre Dumas was building his literary career in Paris, he became an unlikely champion for a new type of firearm. The young author, who would later captivate readers worldwide with novels like The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo, found himself drawn to an innovation in gun design: the Lefaucheux breech-loading system.

His endorsement of the Lefaucheux gun carried particular weight because he proved to be more than just an enthusiastic owner. Through his travel writings, Dumas revealed himself to be an accomplished marksman who regularly demonstrated the weapon’s capabilities across Europe. From Swiss shooting competitions to Russian hunting expeditions, he took pleasure in showing these innovative French firearms to interested audiences.

His enthusiasm stemmed from first-hand experience with this advancement in firearms design. While traditional guns of the time were slow and cumbersome to load, the Lefaucheux system offered new possibilities that appealed to both sportsmen and soldiers. For Dumas, it represented the perfect marriage of practical innovation and refined engineering.

What made Dumas an effective advocate was his combination of practical expertise and literary skill. In his travel writings, he described both the technical aspects of the Lefaucheux system and his experiences demonstrating it to skeptical audiences. His detailed accounts and public demonstrations helped document this French innovation’s reception across Europe, making him an unexpected but notable figure in firearms history.

The Innovation

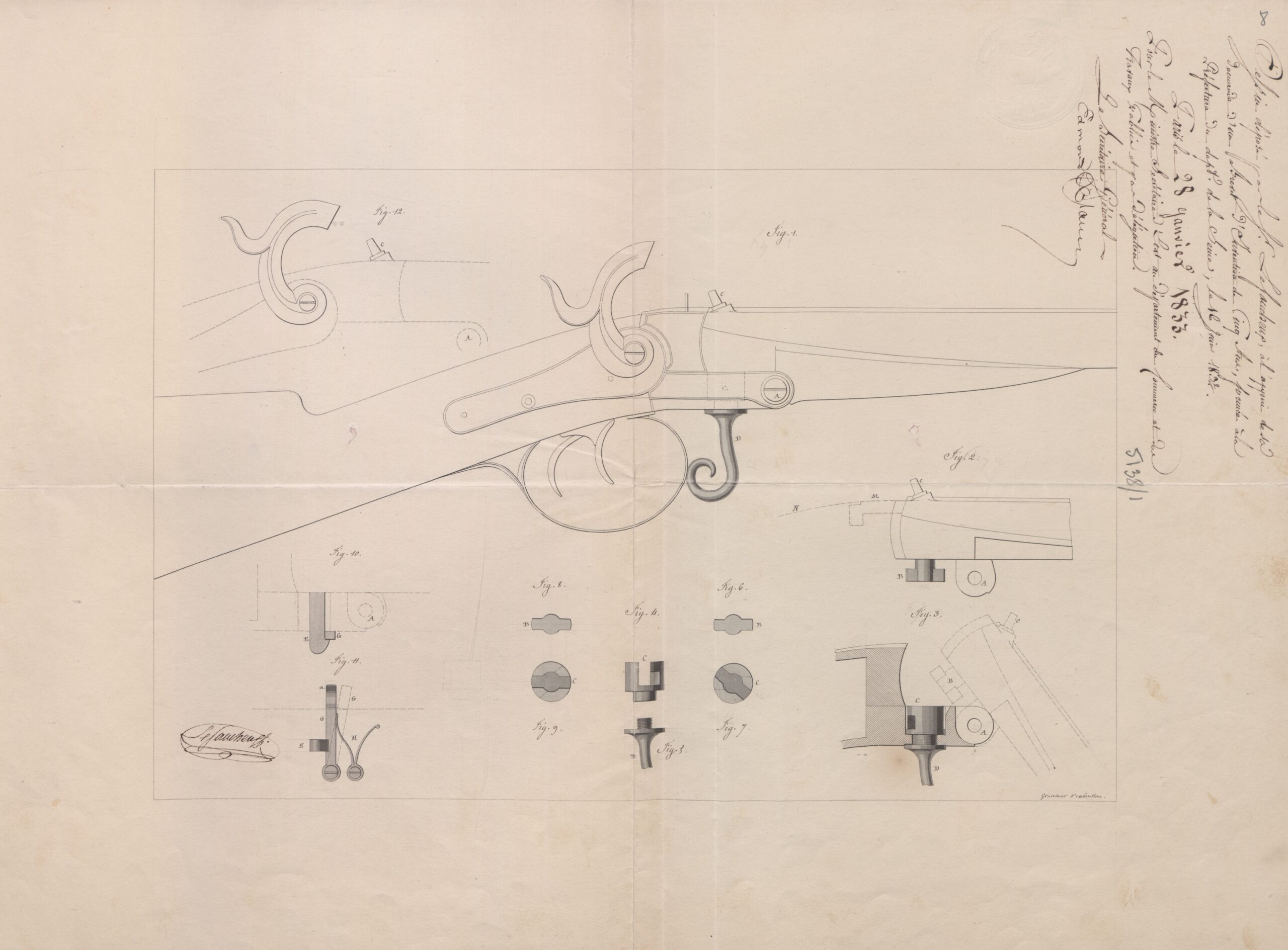

In June 1832, Parisian gunsmith Casimir Lefaucheux walked into the patent office with designs for a new type of firearm. His concept was elegantly simple: a barrel that could pivot open on a hinge. By January 1833, he had secured patent number 5138 for this breech-loading design, which used a T-shaped piece and C-shaped catch to lock the barrel firmly in place after loading.

Lefaucheux spent the next three years refining his invention through a series of patent additions. He improved how the barrel aligned with the stock and developed more secure locking mechanisms. But it was his fourth patent addition in 1835 that marked his most clever innovation: the pinfire cartridge. This new ammunition contained its own primer, activated by a small pin that protruded from the cartridge base. When the gun’s hammer struck this pin, it ignited the primer inside. The cartridge’s metallic base, which could be made of copper, tinplate, or lead, contained all the gases from firing.

To understand why this mattered, consider how other guns of the time worked. A shooter had to measure powder, use a ramrod to push it down the barrel, add wadding, insert a bullet, and place a percussion cap on the outside of the gun. This was time-consuming work that demanded concentration and a steady hand. Rain or movement made the process even more difficult.

Lefaucheux’s system simplified everything. A shooter opened the barrel, placed a single pre-made cartridge inside, and closed it. The integrated primer meant no more separate percussion caps to fumble with or lose. The metallic cartridge base prevented gas leakage, making the gun safer to use. Even in poor weather, the ammunition remained reliable because the primer was protected inside the cartridge rather than exposed on the gun’s exterior.

Hunters and sport shooters particularly appreciated these practical benefits. Double-loading accidents, common with muzzleloaders when a shooter forgot whether they had loaded the gun, became impossible with the break-action design. One could simply open the barrel and check.

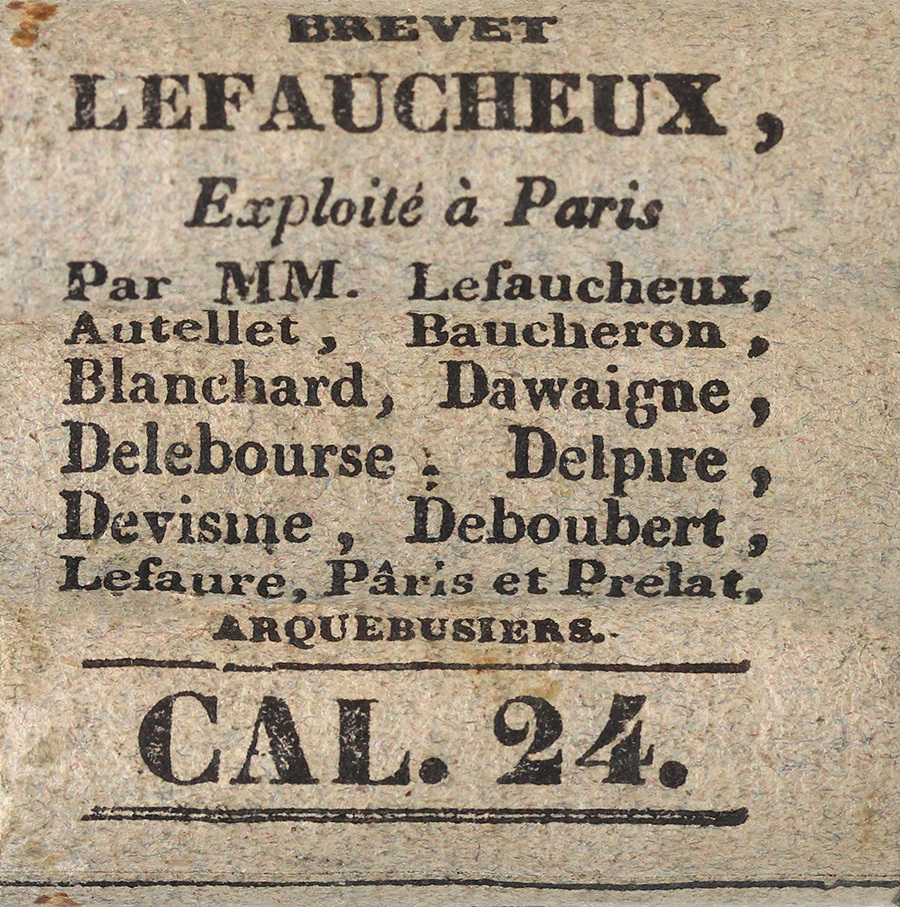

Recognizing the commercial potential of his design, Lefaucheux began licensing his patent to premier Parisian gunmakers in 1833. Among the first licensees were some of the finest names in French gunmaking: Jean Autellet, Jean Pierre Baucheron, and notably, Louis-François Devisme. Each would bring their own interpretation to Lefaucheux’s innovation, but none would combine artistic excellence with technical precision quite like Devisme.

Devisme: The Master Craftsman

Louis-François Devisme opened his Paris workshop at 12 rue du Helder in 1830, at the age of just twenty-four. A student of Deboubert, who had worked alongside the legendary Boutet at the Manufacture de Versailles, Devisme quickly established himself as one of France’s premier gunsmiths. When he acquired a Lefaucheux license in 1833, he immediately began refining the design, improving the precision of the breech mechanism and developing more reliable locking systems.

The gun in our collection exemplifies Devisme’s technical and artistic achievements. The damascus barrels, with their distinctive pattern-welded steel, bear Devisme’s maker’s mark “DEVISME A PARIS” surrounded by scrolling acanthus leaves and fine line engraving. The breech mechanism, though following Lefaucheux’s basic patent, shows Devisme’s improvements in its precise fitting and smooth operation. Gold inlay highlights the maker’s name.

His attention to both technical precision and aesthetic detail earned him recognition at the 1834 Paris Exhibition of Industry, marking the beginning of three decades of accolades including silver medals in 1839 and 1841, and further honors at exhibitions through 1867. This consistent excellence attracted notable clients including Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, King Louis-Philippe of France, and later, several Confederate generals during the American Civil War.

By the time he retired to Argenteuil in 1873, Devisme had been awarded the Légion d’Honneur and numerous foreign decorations. Each piece that left his workshop, whether destined for royalty or sports shooting, received the same exacting attention. This standard is clearly visible in our example.

Dumas’s Endorsement and Adventures

Alexandre Dumas was more than just a casual user of Lefaucheux firearms. His experiences with these innovative weapons would span decades, beginning with a dramatic demonstration in Switzerland.

The Swiss Shooting Competition (1834)

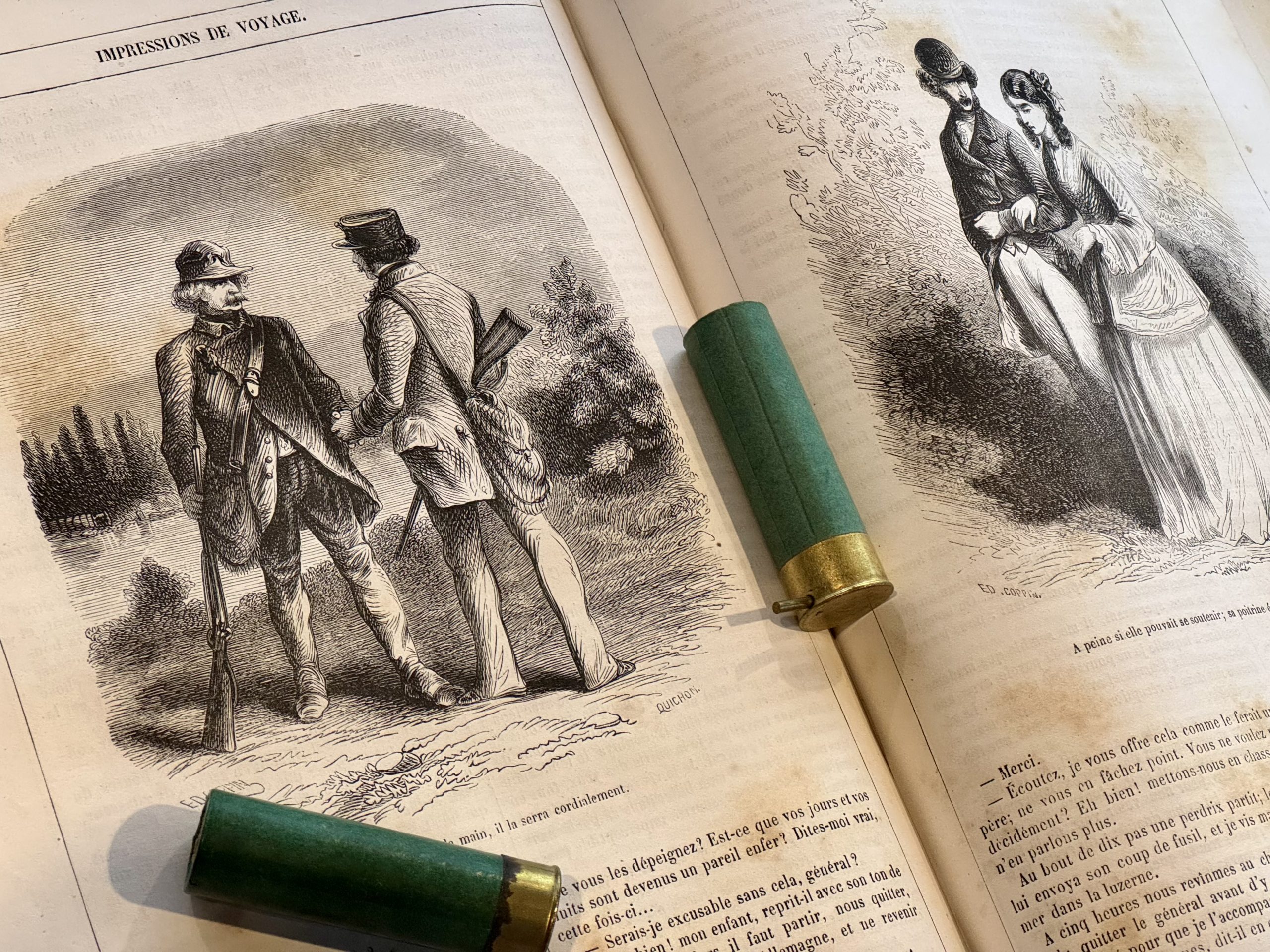

That same year, Dumas put his Lefaucheux to the test at a shooting competition in Sarnen, Switzerland. The scene he described captures both the drama of the moment and the technical superiority of his French firearm. As he approached the firing line, he noted his heart was pounding “like during my first theatrical performances.” A great silence fell over the crowd, and one of the most skilled local shooters lent him a gun. The careful attention paid to loading this traditional weapon, Dumas observed, proved they took the competition seriously.

When Dumas hit his mark, the response was immediate. The target keeper emerged with a flag, waving it in salute as the crowd burst into applause. But it was his personal weapon that truly captured their attention:

“The shooters surrounded me to examine my carbine; it was a beautiful weapon by Lefaucheux, perfected by Devisme, and loaded from the breech. This new invention was completely unknown to these marksmen; as such, they could not understand its mechanism, examining it with all the curiosity of true novices.”

To demonstrate the gun’s capabilities, Dumas loaded a cartridge and showed them the unique pin mechanism. When he fired, the ball embedded itself so deeply into the trunk that a rod entered one and a half inches into the hole. The Swiss shooters were left “paralyzed by astonishment that one could invent something superior to the armories of Lausanne and Bern.” To further prove the gun’s worth, Dumas approached a window and shot two swallows in rapid succession.

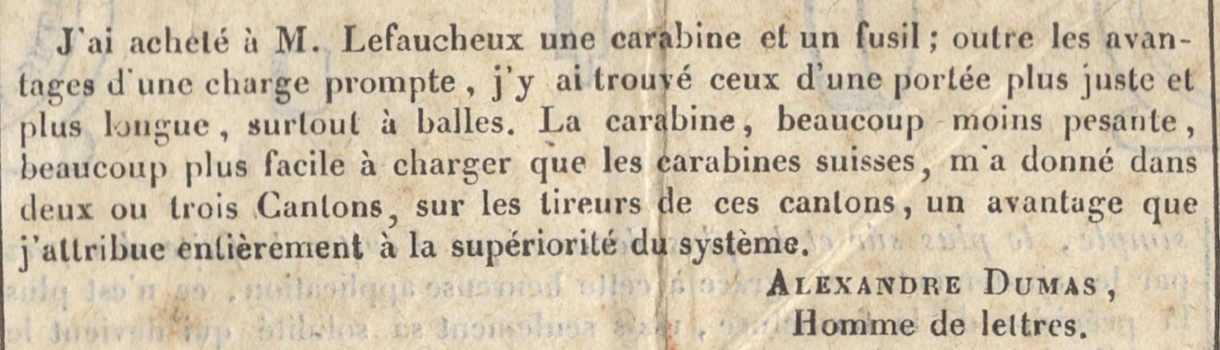

After such successes, Dumas penned an enthusiastic testimonial for Lefaucheux:

“I have bought from Mr. Lefaucheux a carbine and a shotgun; besides the advantages of a quick loading, I have found in them a more accurate and longer range, especially with bullets. The carbine, much less heavy, much easier to load than the Swiss carbines, has given me in two or three Cantons, over the shooters of these cantons, an advantage that I attribute entirely to the superiority of the system.”

This endorsement from one of France’s rising literary stars proved valuable to Lefaucheux. In the only known standalone broadside advertisement for his firearms, a striking two-sided document preserved in the Lefaucheux Museum archives, the gunmaker prominently featured Dumas’s testimonial alongside endorsements from established military figures and sportsmen. The novelist’s enthusiasm for these weapons would continue to serve as informal advertisement throughout his travels over the next twenty-four years.

The Sicilian Guide (1835)

In Sicily, while traveling through the countryside, Dumas met a guide named Salvadore. As we had invited Salvadore to have breakfast with us, Dumas noted, it took some preliminary formalities before the guide finally agreed. By the meal’s end, he had become more talkative than at their departure. When Jadin, Dumas’s companion, asked to make Salvadore’s portrait, the guide agreed with good humor, draping his cloak over his left shoulder and posing with the natural composure of someone used to such requests.

During this interlude, Dumas took his rifle and shot a rabbit that had unwisely ventured from its burrow. This small demonstration gave Salvadore the opening to examine the firearms he had been curiously eyeing. As Dumas wrote:

“This gave Salvadore the opportunity to ask us for permission to examine our rifles, something he had not dared to do earlier despite his curiosity. He took them and inspected them like a man familiar with firearms; however, as they were Lefaucheux-system rifles, the mechanism was entirely unknown to him.”

Dumas was happy to demonstrate, switching out his rabbit-shot cartridges for partridge-shot cartridges and, throwing two piastres into the air, hit both. Salvadore went to pick up the piastres, retraced the lead marks, and shook his head up and down, like a true connoisseur appreciating the shot. When offered the chance to try himself, Salvadore replied he had never been much of a wing shooter but would demonstrate his skill at a fixed target. Taking aim at a small white stone about the size of an egg, located a hundred steps away in the middle of the path, he fired and shattered it into a thousand pieces.

The Cossack Demonstration (November 7, 1858)

Twenty-three years later, Dumas’s enthusiasm for his Lefaucheux firearms remained undiminished. While journeying through Russia, he encountered a group of Cossacks who had fought in the Crimean War. One had told his companions what they considered “a fabulous story about a six-shot pistol.” Near Touravnovski on November 7, Dumas demonstrated his Lefaucheux rifle during a partridge hunt. A flight of partridges had settled in a bush; he got down from his carriage and approached them. When they flew off, he shot one and hit a second, but managed to reload so quickly that, before it had taken ten steps on foot, he shot it again with his third shot.

The Cossacks were amazed, asking if his rifle was “a three-shot gun, like my revolver was six-shot.” Dumas showed them how the breech-loading mechanism allowed for continuous firing. “Twelve cartridges were spent,” he wrote, “but with this small sacrifice, I left in the village a memory that, I believe, will not soon fade.”

The Caucasian Prince (Late 1858)

His Russian journey led him to the Caucasus, where he encountered a young prince who proved to be one of his most enthusiastic students. The scene unfolded in a courtyard where, remarkably, the prince observed the demonstration while leaning on a large tame stag, which seemed, on its own, to take an interest in their conversation. A huge black ram, tied four steps away, paid only secondary attention to their discussion, content to lift its head from time to time and look at them indifferently.

The young prince showed remarkable aptitude for the new system, quickly grasping both how the breech mechanism worked and how the cartridge was manufactured. After watching Dumas demonstrate the weapon just once, he loaded it himself without hesitation. “It was enough for him to have seen me do it once,” Dumas noted, “to imitate me in every detail.”

Despite Dumas’s encouragement to shoot offhand, the prince insisted on using a barrel for support. “Easterners shoot well,” Dumas observed, “but almost always, they shoot only under such conditions.” After some initial misses and Dumas’s suggestion to add an aiming point, the prince succeeded brilliantly, striking the target dead center.

His success with the gun so delighted him that he called out to his father, watching from the balcony, “Now you can let me go on an expedition with you, since I know how to fire a rifle.” Moved by the young man’s enthusiasm, Dumas promised to send him his own Lefaucheux rifle from Paris. “I already loved you before knowing you,” the prince responded, “but I love you even more now that I know you,” and threw his arms around Dumas’s neck.

Through these encounters, meticulously recorded in his travel writings, Dumas provided invaluable first-hand accounts of how this French innovation was received across Europe. From Swiss shooting ranges to Russian steppes, from Sicilian hunting grounds to Caucasian courtyards, he documented the technical superiority of the Lefaucheux system alongside the human reactions to encountering such innovation.

Legacy and Influence

The story of the Lefaucheux system represents a remarkable convergence of innovation, craftsmanship, and advocacy. The basic principles Lefaucheux patented in 1832, including the hinged breech, the self-contained cartridge, and the precise locking mechanism, became fundamental elements of firearm design. Modern break-action shotguns still follow his basic pattern, and his pioneering work with integrated cartridges laid the groundwork for subsequent ammunition development.

Devisme’s interpretation of these innovations demonstrated how technical advancement could coexist with traditional gunmaking artistry. His exquisitely crafted firearms proved that new manufacturing techniques need not compromise aesthetic values. Other manufacturers followed his lead, maintaining high standards of decoration and finish even as production methods evolved. The marriage of art and engineering that Devisme achieved with his Lefaucheux guns influenced fine gunmaking well into the 20th century.

Dumas’s role in this story is equally significant. His travel writings provided detailed, first-hand accounts of how this French innovation was received across Europe. In Switzerland, Russia, the Caucasus, and Sicily, Dumas demonstrated the new technology to audiences ranging from skeptical marksmen to curious nobles. His accounts captured both the technical details and the human reactions to a changing world. Through his words, we see how new technology spread through nineteenth-century Europe, one demonstration at a time.

Together, these three figures, inventor, craftsman, and advocate, show how technological change actually occurs. Lefaucheux’s patents provided the innovation, Devisme’s workshop proved it could be both practical and beautiful, and Dumas’s demonstrations showed its value in the field. Their intersection in 1830s Paris created ripples that would influence firearms development for generations.

The Lefaucheux gun in our collection, crafted by Devisme in 1835, embodies this convergence of innovation and artistry. Its damascus barrels and engraved surfaces showcase the pinnacle of French gunmaking craft, while its breech-loading mechanism represents a fundamental shift in firearms technology. When visitors handle this piece today, they’re touching the same surfaces that amazed Swiss marksmen, Russian Cossacks, and Caucasian princes in Dumas’s accounts. In its metal and wood, we find the physical intersection of Lefaucheux’s innovation, Devisme’s craftsmanship, and the era of technological change that Dumas so vividly documented.

References & Further Research

Dumas, A. (1834). Impressions de voyage: En Suisse. Paris, France: Hippolyte Souverain.

Annotation: Details Dumas’s impressions of Switzerland, including the 1834 shooting competition in Sarnen. Provides an early example of his enthusiasm for Lefaucheux’s breech-loading system.

Dumas, A. (1842). Le Speronare. Paris, France: Michel Lévy Frères.

Annotation: Offers Dumas’s travel notes on Sicily and the surrounding region. Includes anecdotes about hunting and demonstrating his Lefaucheux-Devisme firearms to curious locals.

Dumas, A. (1859). Le Caucase: Impressions de voyage; suite de En Russie. Paris, France: Michel Lévy Frères.

Annotation: Chronicles Dumas’s travels through Russia and the Caucasus between 1858 and 1859. Contains detailed accounts of shooting demonstrations and interactions with Cossacks and local princes.

Lefaucheux, C. (1832). Brevet d’invention No. 5138: Breech-loading firearm [French Patent No. 5138]. French Patent & Trademark Office.

Annotation: The foundational patent describing Casimir Lefaucheux’s hinged breech-loading mechanism. Illustrates the crucial technical innovation later licensed by Devisme and showcased by Dumas.