Picture a crisp morning west of Paris. A small party of friends and staff gathers at the edge of the royal forests, guns broken open, dogs twisting in circles, everyone talking at once. Our story of that day comes from seven glass plate negatives (gelatin dry plates, each 13 × 18 cm). Think of them as a pocket photo album that survived. The images lead us from the gate, into the woods, and back again with a stag strapped to the carriage.

Not everyone could pass this arch with a gun. These woods belonged to a tradition of regulated access that stretched back to the kings of France. To shoot here you needed land, invitation, or a lease. That sense of privilege hums through the pictures. The men are tidy and warm in wool coats, waistcoats, breeches, gaiters, felt hats, and stout boots. Their guns are pinfire breech‑loaders. The little metal pin that sticks out of the cartridge gives the system its name. It was fast and fashionable in France even as centerfire began taking over.

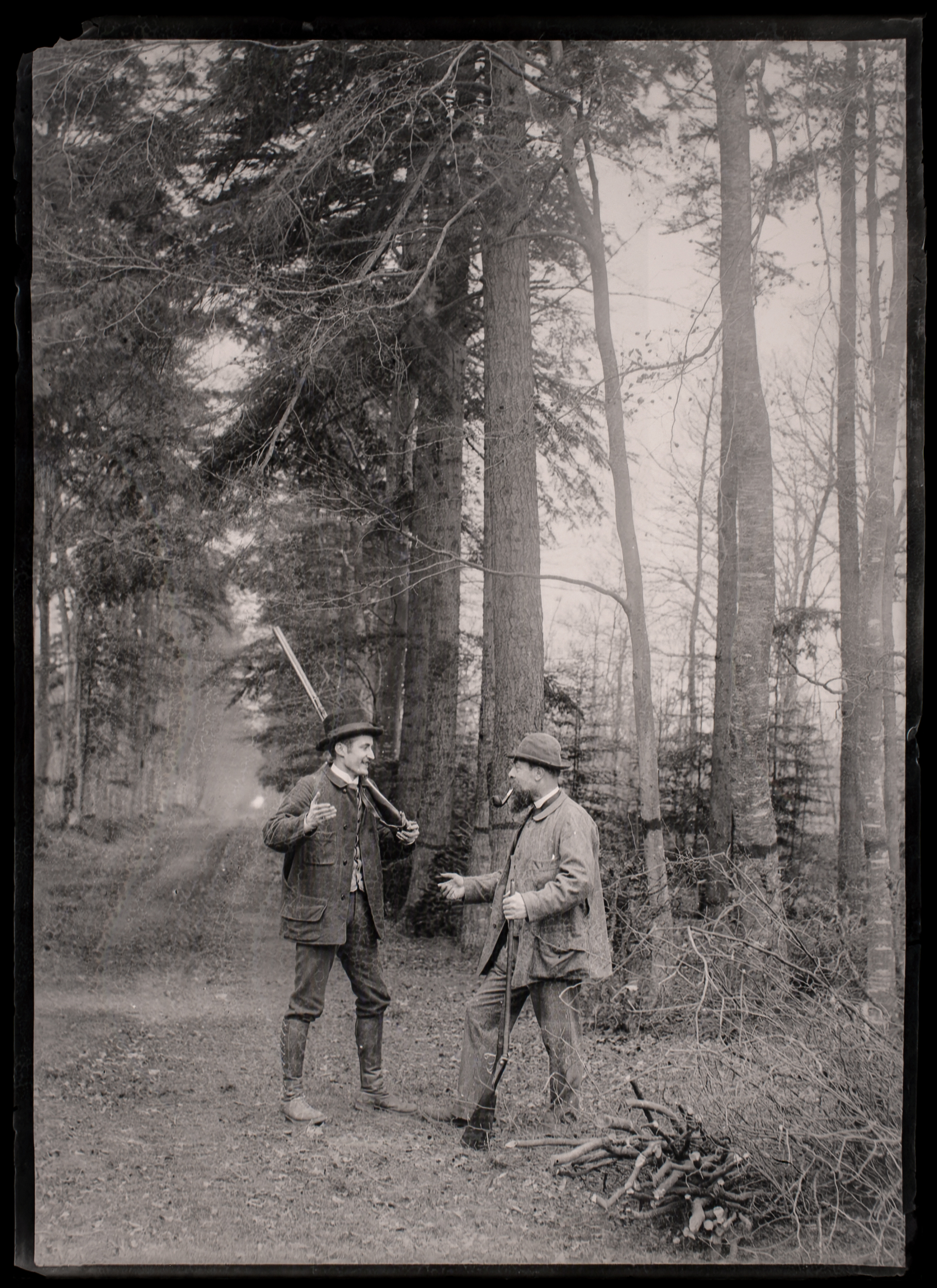

One pleasure of the set is the time it spends on pauses. In these long straight rides the talk is as important as the shots. Etiquette shows in small things. Barrels kept high. Actions open when chatting. Dogs close at heel while the next drive is organized somewhere out of sight. The allées themselves are a signature of Versailles forestry. They run in ruler‑true lines that make the woods feel designed rather than wild.

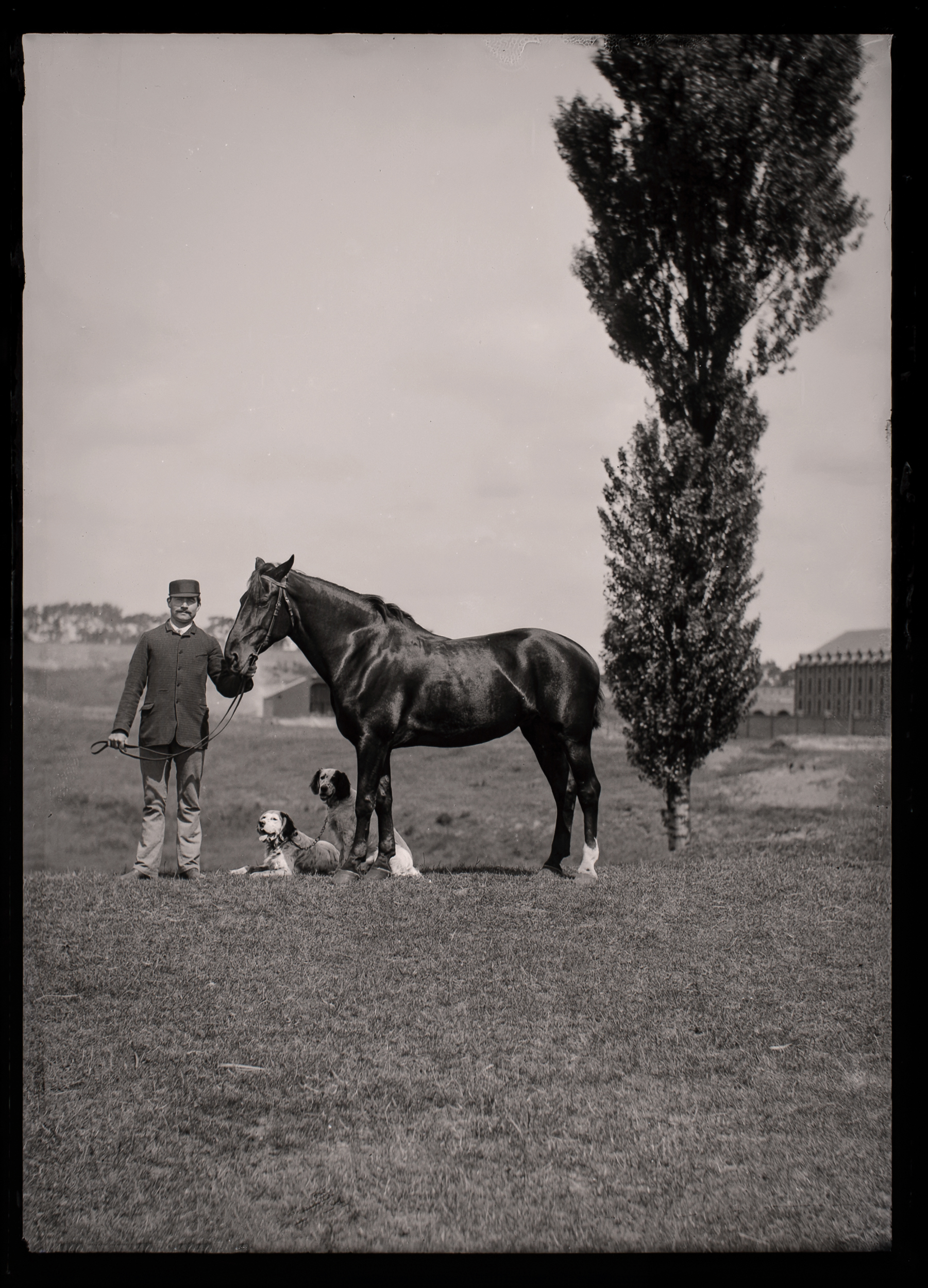

Behind a smooth day stands a lot of quiet work. Horses move guns and guests between stands. Dogs do the finding and retrieving. Staff make sure both behave. One plate is almost a roll call of that support.

Then comes the moment everyone is waiting for. A heavy‑antlered red deer lies on the grass by a clipped hedge. The hunter stands beside it, upright and not theatrical. It is a simple tableau, and that is why it works. This is the picture that makes the day official.

There is celebration too. The party crowds onto a horse‑drawn carriage. The stag is lashed along the side. Wicker hampers are stacked behind the seats. Several men keep hold of their pinfires for the camera. It looks like a magazine cover for the sporting life of the Third Republic.

The album includes landmarks that tie this countryside to the city. One of them is the ivy‑clad windmill at Longchamp in the Bois de Boulogne. If you know the racecourse, you know the area. The cross at the top of the conical cap, the narrow gallery, the long tail‑pole, and the rustic bridge over a stream match views of the site that Parisians loved to stroll past. The picture is a reminder that the same crowd who shot in Yvelines also met to race and promenade at Longchamp.

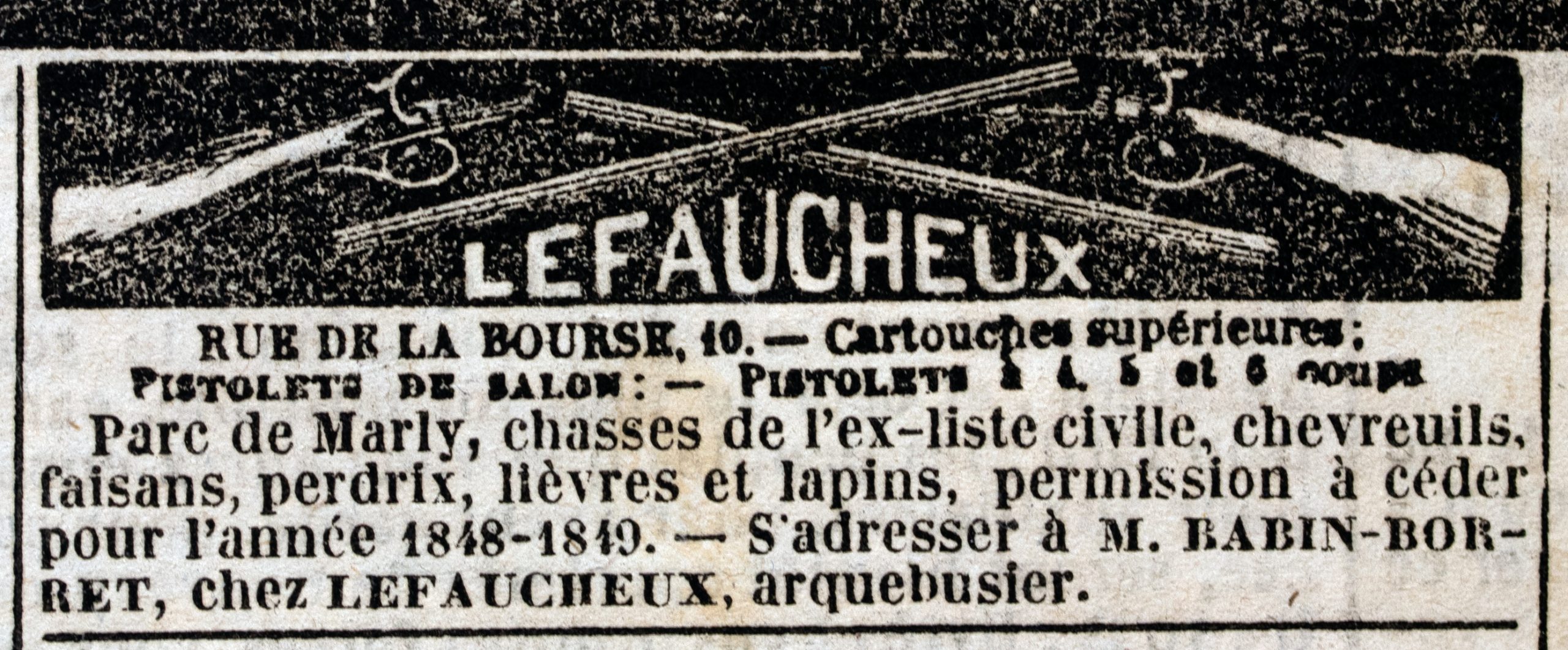

Now to the question of who gets to hunt. Access was never simple and often involved money, influence, or a helpful intermediary. Our collection holds a small but telling printed advertisement from the revolutionary year 1848. It offers shooting in the Parc de Marly, part of the former civil list lands, and directs interested customers to inquire at the shop of Lefaucheux, arquebusier. Yes, that Lefaucheux, the family name behind the famous pinfire system. Gunsmiths did not just sell guns. They opened doors.

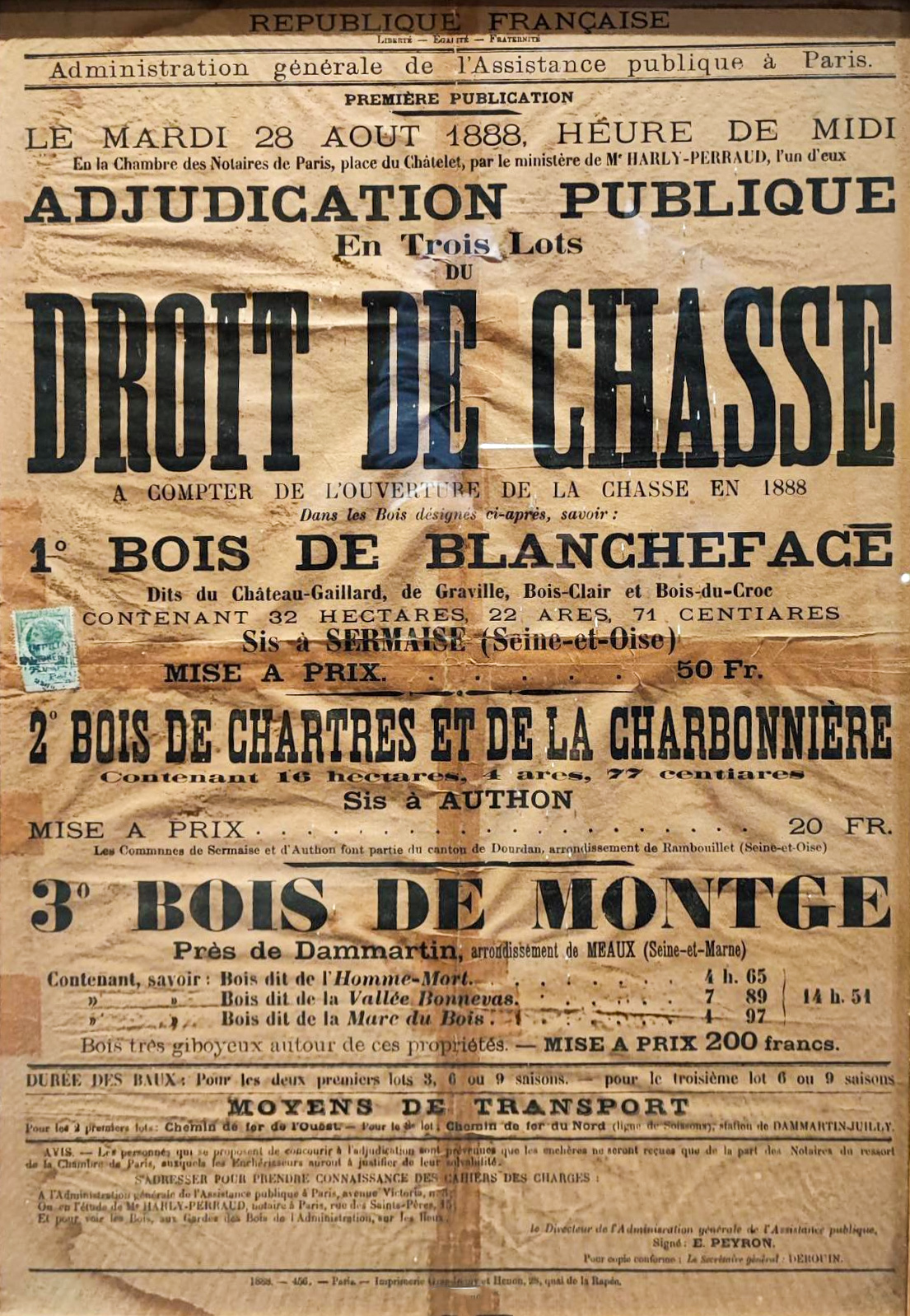

By the late 1880s access had become even more formal. Public bodies leased hunting rights by auction. It kept control tight and guaranteed revenue, and it meant that many of the finest woods around Paris remained the preserve of those who could pay. The poster below advertises one such sale, with lots measured in hectares and francs.

Seen together, the plates feel less like a police report of who shot what and more like an invitation to step into that world for a day. You cross the gate, you share the stories in the rides, you watch the dogs quiver, and you stand quietly for the trophy picture. The technology matters only as part of the atmosphere. Pinfire guns click shut. Gelatin dry plates make it possible to capture the low light under beeches and firs. The real pleasure is the sense of movement through a landscape where privilege, planning, and sport meet.

That is why the set is a favorite here. In nine images, including the two pieces of ephemera, you get a tour of how hunting around Paris actually worked. It was social, organized, and carefully controlled. It was also beautiful. And for a handful of friends on a certain morning, it was a very good day out.